As we announced in our summer update blog, we have a revamped toolchain! cargo-v5 is the replacement for cargo-pros. Instead of depending on pros-cli for uploading and terminal, cargo-v5 uses our new library vex-v5-serial which is a complete reimplementation of the V5 Serial Protocol written in 100% Rust. It supports wired, controller, and direct Bluetooth, sometimes called btle, connections.

Reimplementing the Brain’s serial protocol was no small feat! It would have been much harder without amazing references like vexrs-serial (vex-v5-serial was originally a fork of this repo but we eventually completely rewrote it), v5-serial-protocol, and, last but not least, pros-cli. I want to give a huge thanks to all of these projects for open sourcing their code.

This post will be going over both the details of the V5 Serial Protocol and the implementation details of vex-v5-serial. My aim is to make this as understandable as possible for everyone with basic systems programming knowledge, regardless of if you know anything about VEX robotics.

The Serial Protocol

First off, what exactly is this V5 Serial Protocol? In short, V5 Serial Protocol is what allows your computer to communicate with your V5 Brain. This is what tools like pros-cli and VEXcode use to upload programs and view terminal output among other things. Despite being named a serial protocol, it can function across both USB serial connections and wireless Bluetooth connections.

The V5 Brain Serial Protocol is a binary protocol consisting of Command (device-bound; your computer sends a Command packet to the brain) and Response (host-bound; your Brain sends a Response packet to your computer) packets. Every Command packet has a corresponding Response packet. There are two categories of packets: CDC and CDC2 (CDC stands for communications device class). All Command packets start with the device-bound header ([0xC9, 0x36, 0xB8, 0x47]) and a one byte ID. Similarly, Response packets start with the host-bound packet header ([0xAA, 0x55]) and a one byte ID with the same value of the corresponding Command packet. The rest of the contents of Command and Response packets change based on what category of packet it is, but both packets types can optionally have a payload depending on the packet type. CDC packets are sometimes called simple packets, and CDC2 packets are sometimes called extended packets.

CDC Packets

CDC Command packets contain:

- the device-bound packet header,

- a one byte ID unique to every CDC packet,

- and finally the payload data.

Currently all supported CDC command packets do not have any payload data so they just end after the ID. One example of a CDC command packet is Query1Packet. It has an ID of 33, so it would be encoded as [0xC9, 0x36, 0xB8, 0x47, 0x21].

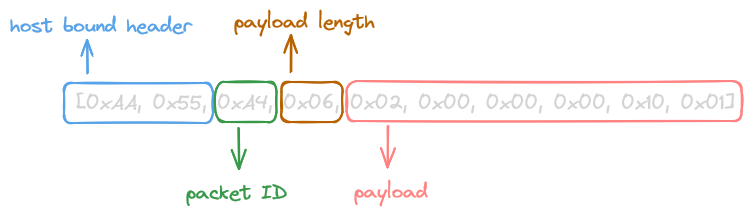

Host-bound CDC packets contain a bit more info. They contain:

- the host-bound packet header,

- an ID,

- a variable width integer that can be stored in 8 or 16 bits (from now on I will refer to this type as a

VarU16) storing the size of the payload, - and the payload data.

GetSystemVersionReplyPacket is host-bound CDC packet. This diagram shows the structure of the packet with reasonable byte values:

VarU16s are stored in an interesting way. When the number stored in the VarU16 is lower than 128, the number is stored as if it was a regular u8; however, when the number is greater than 128, it is stored in two bytes and the most significant bit is set to 1. The number 50 would be encoded in a VarU16 as 0b00110010 taking up 8 bits, but 200 would be encoded as 0b1000000011001000 taking up 16 bits.

CDC2 Packets

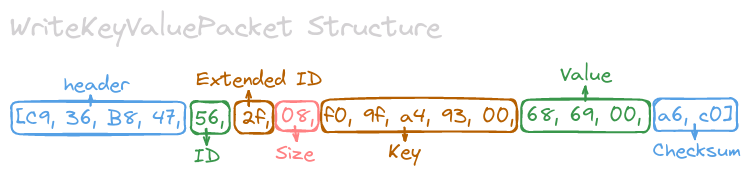

CDC2 packets make up the vast majority of packet types. The biggest differences between CDC2 packets and CDC packets are that CDC2 packets include extended IDs and CRC16 checksums.

Device-bound CDC2 packets contain:

- the device-bound packet header

- a one byte ID which is the same for most CDC2 packets

- a one byte ‘extended’ ID unique to each CDC2 packet type

- a

VarU16with the size of the payload, the payload bytes - a CRC16 checksum of the entire packet.

One simple CDC2 packet type is WriteKeyValuePacket. Its payload stores two strings, one for the key and the other for the value. This packet would look like this encoded:

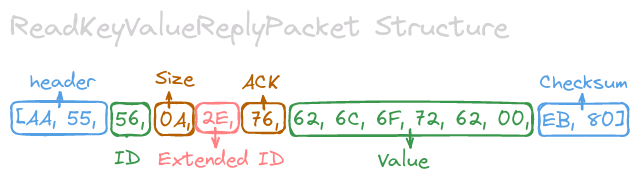

Host-bound CDC2 packets are very similar with the addition of an ACK code just after the header. When vex-v5-serial decodes CDC2 packets, it will first decode the entire packet and then later the ACK code will be checked. If it is not Cdc2Ack::Ack an error will be thrown with more info about the cause of failure. Here is the structure of one of these packets:

Irregular Packets

Notably, there is one packet type that doesn’t cleanly fit into CDC or CDC2. This one packet type is ReadFileReplyPacket. On failure, it will contain:

- an ID,

- an extended ID,

- an ACK code,

- and a CRC16 checksum.

However, on success it will contain:

- an ID,

- an extended ID,

- the address that was read from,

- the data that was read,

- and a CRC16 checksum.

It doesn’t fit in with CDC2 because it doesn’t always have an ACK code, and it doesn’t fit with CDC because of its extended ID.

Connection to the Brain

There are three ways for a host machine to connect to a Brain:

- Direct wired connection: A USB connection directly from your computer and into the Brain. This is by far the fastest connection type. This type of connection has 2 separate serial ports. These serial ports are named system and user. The system port is used for communicating with the Brain over the serial protocol, and the user port is used for viewing user program stdio output (this is often called the debug terminal). In the communication section we talk about distinguishing these two serial ports.

- Controller: A USB connection to your controller which can be paired to your Brain via VEXnet, Bluetooth, or even a cable. This connection type is very similar to a direct connection with one exception: This method of communication only has one serial port (this port is often named a controller port). This port acts the same way as the system port in a direct brain connection. For this reason, stdio output has to be received with a

UserFifoPacket. The response to this packet contains the incoming stdout buffer. - Bluetooth: A direct bluetooth connection to a V5 Radio. This connection type functions similarly to a controller connection, but instead of being over serial, its over Bluetooth. For this connection type to work, you must have your radio mode set to Bluetooth and data enabled in your Brain settings. This is by far the least secure connection type; when possible, you should keep data turned off.

How vex-v5-serial Works

vex-v5-serial is a complicated project so the code is split into several distinct sections that all handle separate things.

Not only does this improve code quality, but it also has the added benefit of allowing for features that enable all of these different sections. For example, the connection feature toggles the connection code.

Packets

There are about 100 unique packets types, whether Brain or host-bound. Because of that huge number, we keep all of our packets in submodules of a larger packets module.

In order to encode and decode packets, vex-v5-serial has 4 base packet types representing every kind of packet in the protocol (excluding ReadFileReplyPacket): CdcReplyPacket, Cdc2ReplyPacket, CdcCommandPacket, and Cdc2CommandPacket.

These types have type parameters for the packets ID, extended ID (if it has one), and the payload type. A payload type of () signifies that the packet type has no payload. These parameters allow for every packet type to be easily created like this:

// This would have a `Decode` implementation if it were a real payload.// See the Encoding and Decoding section for more infopub struct ExampleReplyPayload { foo: u8, bar: u8,}// 90 is the ID for this example packetpub type ExampleReplyPacket = CdcReplyPacket<90, ExampleReplyPayload>;In order to receive a packet, vex-v5-serial first decodes the header of the incoming packet and the length of the incoming packet. If the header and length is valid, it will asynchronously read ‘length’ bytes into a buffer, and then decode that into the packet type given by the user.

Encoding and Decoding

We use two traits for encoding command packets and decoding response packets. These two traits are Encode and Decode. Encode takes a Command packet and encodes it into a byte vector that can be sent to the Brain. Inversely, Decode takes a byte vector and constructs a Response packet with it. For any language nerds out there, Decode is an LL(1) parser. The Decode trait isn’t perfect as it can struggle to decode arrays and strings that aren’t null-terminated (the solution to this is the third, less commonly used, trait: SizedDecode), but for how simple it is you can make some surprisingly capable and speedy parsers in a really ergonomic way! Take the following basic parsing example based off of our real code:

// Decode is implemented for a variety of primitives,// including most integer types and [D; N] where D implements Decodestruct ResponsePacket<Payload: Decode> { pub header: [u8; 2], pub payload: Payload,}impl<Payload: Decode> Decode for ResponsePacket<Payload> { fn decode(data: impl IntoIterator<Item = u8>) -> Result<Self, DecodeError> { let mut data = data.into_iter(); let header = Decode::decode(&mut data)?; let payload = Payload::decode(&mut data)?; Ok(Self { header, payload }) }}struct ExamplePayload { data: u8}impl Decode for ExamplePayload { fn decode(data: impl IntoIterator<Item = u8>) -> Result<Self, DecodeError> { let data = u8::decode(data)?; Ok(Self { data }) }}// This is the type that users can use in functions like receive_packet.type ExampleResponsePacket = ResponsePacket<ExamplePayload>The beauty of this approach is that every packet only needs to implement decode for a payload type and the rest of the decoding is handled by higher level wrappers such as ResponsePacket in this example. This applies to the Decode implementations on primitives as well. All decoding eventually goes lower and lower level until you finally hit the u8 Decode implementation which simply calls next on the data iterator and returns a DecodeError::PacketTooShort error if there is no byte to consume.

The Encode trait is intentionally similar in design to the Decode trait. Here is a simplified example of its usage:

struct CommandPacket<Payload: Encode> { pub header: [u8; 4], pub payload: Payload,}impl<Payload: Encode> CommandPacket<Payload> { pub fn new(payload: Payload) -> Self { Self { header: [1, 2, 3 ,4], payload } }}impl<Payload: Encode> Encode for CommandPacket { fn encode(&self) -> Result<Vec<u8>, EncodeError> { let mut encoded = Vec::new(); encoded.extend_from_slice(self.header); encoded.extend(self.payload.encode()?); Ok(encoded) }}pub struct ExamplePayload { data: u8}impl Encode for ExamplePayload { fn encode(&self) -> Result<Vec<u8>, EncodeError> { Ok(vec![self.u8]) }}// This type can be constructed to be sent to the brain like this// ExampleCommandPacket::new(ExamplePayload { data: 10 })type ExampleCommandPacket = CommandPacket<ExamplePayload>;Encoding boils down to extending a vector at the end of the day, not super interesting. Here, encoding can never fail, but there are some cases where that isn’t the case. Specifically in the case of vex-v5-serial encoding can fail when you attempt to encode a number larger than the 15bit integer limit as a VarU16 or when you attempt to encode a String longer than the maximum length into one of the many string types in the serial protocol.

Connection

The connection module houses all of the low level communication with the brain over a serial or Bluetooth connection. This is how we are able to send and receive bytes from the brain.

Currently we have a Connection trait which provides a convenient API for communication with the Brain. You can send and receive packets, execute commands (see the commands section), and perform packet handshakes. A packet handshake is a convenient way to send a packet and receive a corresponding reply from the brain with a few added features like timeouts and retries.

Port Type Inference

I talked about the differences in communication types a while ago, but heres a little refresher: A USB connection directly to the Brain has two separate serial ports (a connection to the controller only has one). One of these ports is for the ‘debug terminal’ (user port) which allows you to view the stdio output from user programs, and the other is for the serial protocol (system port). For this reason, it is necessary for vex-v5-serial to tell the two ports apart from each other.

If you try to communicate with the Brain over the user port nothing will happen. There are a couple ways to tell these ports apart, but the one that vex-v5-serial uses is the ‘interface ID’ of the port. Unfortunately, the serialport crate, which we use to get information about and connect to serial ports, incorrectly gets this information from MacOS machines. This forces us to do a workaround where we parse the interface ID from the filename of the serial port. Windows has a similar issue but for a completely different reason. The Windows serial port drivers are horrible and don’t provide a huge amount of information that should be available. On Windows we fall back to the numeric order of the COM port names which appear to always be in the same order.

Commands

Commands are high level abstractions over common sequences of packet exchanges. A great example of this is the UploadProgram command. Uploading a program requires uploading two or three files depending on if you are uploading a monolith (uploading a file is a complicated task on its own), generating an INI config file with information about the program, compressing the program files with GZip, and finally sending multiple ExitFileTransferPackets with different exit actions. Whew… Thats a lot.

Commands can save you a huge amount of time because all of that complicated logic is distilled down to a simple function call like this:

let mut connection = ...connection .execute_command(UploadProgram { // Program upload configuration here ... }) .await?;That’s certainly quite a bit easier than the several hundred lines of code that the UploadProgram and UploadFile commands take up.

Future Plans

Right now we are only utilizing vex-v5-serial for cargo-v5 but that will change soon!

We already have big plans for how we will use it in the future.

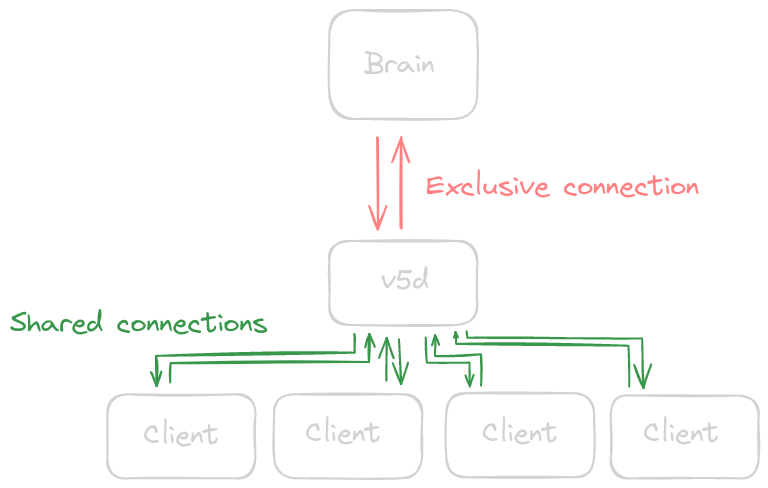

v5d and v5ctl

In the future, we plan on using vex-v5-serial to implement a V5 Brain Daemon (v5d) which will allow sharing a connection with the brain. Multiple programs will be able to communicate with the brain even though only one program can connect to it at a time.

v5ctl will be a general purpose CLI tool that supports most features of the V5 Serial protocol. Once v5d is finished, cargo-v5 will be switched to using v5d. You can find the repo for both v5d and v5ctl here.

LemLink

LemLink is a project that is being developed by the LemLib and vexide teams. The current plan is for it to be backwards compatible with pros-cli but with better dependency management. It will also be implemented in terms of v5d. This will make it easier to run multiple LemLink commands simultaneously. The LemLink repo is here.